Self-Distilled Reasoner: On-Policy Self-Distillation

As intelligence scales, learning need not rely solely on external supervision; sufficiently capable systems can refine themselves by reflecting on outcomes.

Much like a student reviewing solutions, rationalizing them, and correcting prior mistakes, an LLM can be conditioned on privileged info (e.g., correct solution or a reasoning trace) and supervise its weaker self—the version without such access—by matching the privileged-info-induced distribution from itself.

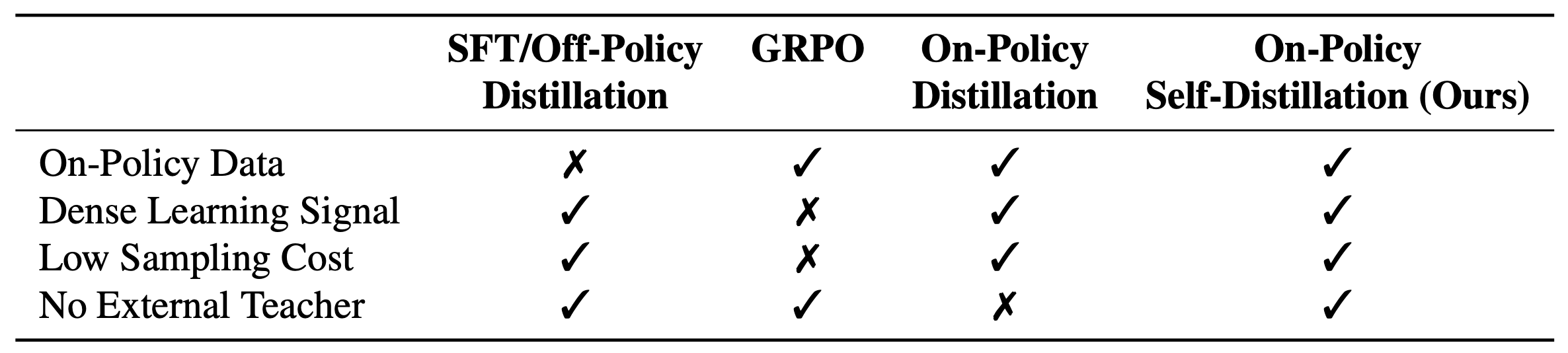

The Challenge of Current LLM Training Paradigms

LLMs have shown impressive abilities in reasoning tasks, but finding more efficient and effective ways to train them remains an active area of research. Current popular approaches come with their own trade-offs:

Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) uses expert demonstrations for training but might encounter exposure bias

Reinforcement Learning (RL) methods, such as Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO)

Knowledge Distillation traditionally provides dense token-level supervision from a teacher model but relies on off-policy data

Core Insight

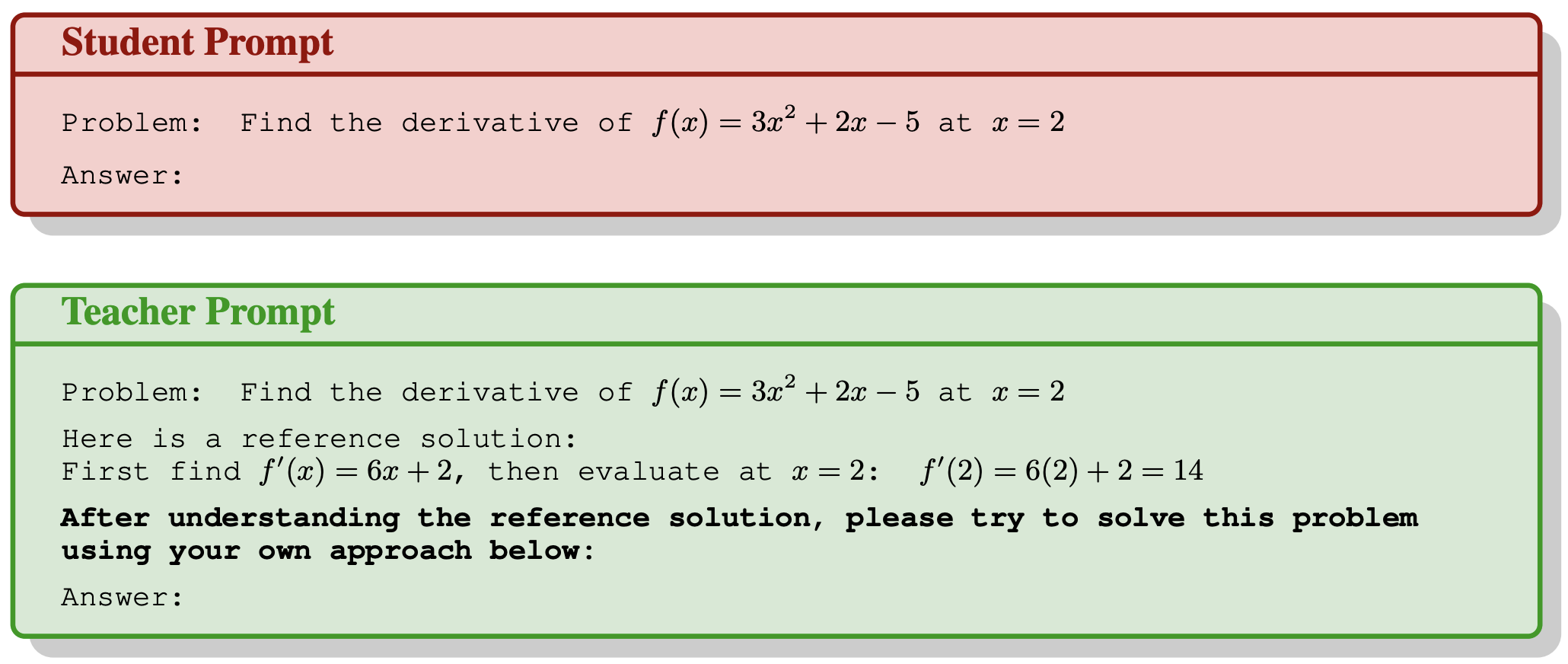

Given that modern LLMs already exhibit strong reasoning capabilities, we ask this research question: Can a model effectively serve as its own teacher through self-distillation? Specifically, when provided with ground-truth solutions as privileged information, can a sufficiently capable model rationalize the reasoning steps and provide dense token-level supervision to guide its weaker self—the version without access to privileged information?

Our approach draws inspiration from human learning. When students struggle with a problem, rather than relying on extended trial-and-error, they can examine the correct solution, understand the reasoning steps, and identify where their own reasoning went wrong. Prior work has shown that for LLMs, evaluation is often easier than generation

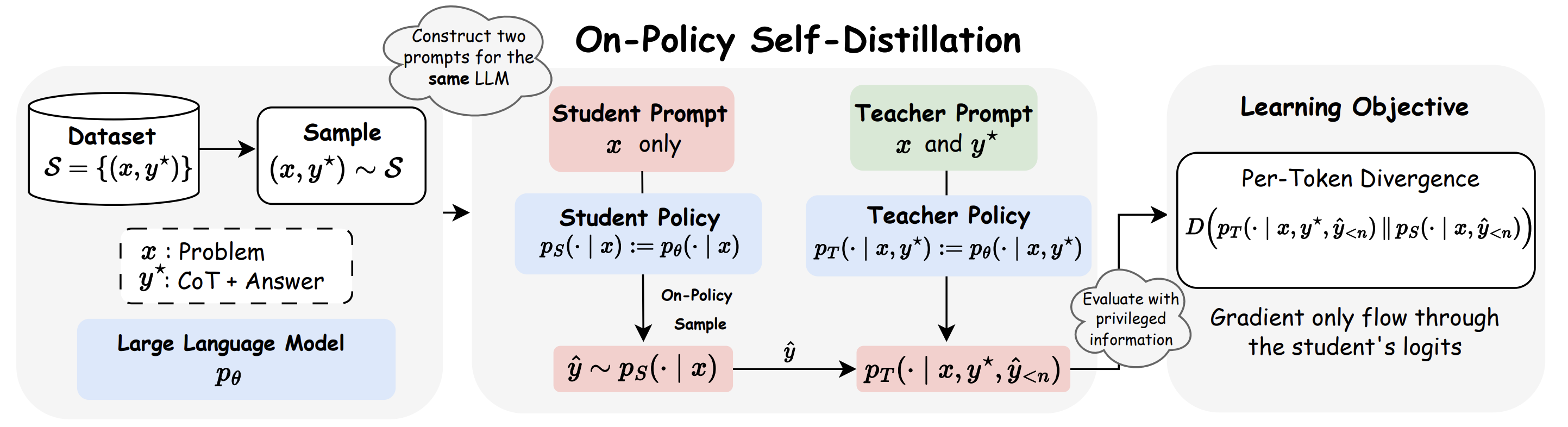

We show that the answer is yes through proposing On-Policy Self-Distillation (OPSD), where a single model plays two roles:

- Student policy \(p_S(\cdot \mid x)\): observes only the problem \(x\), replicating inference-time conditions

- Teacher policy \(p_T(\cdot \mid x, y^*)\): receives privileged access to the ground-truth solution \(y^*\)

Critically, both policies share the same parameters but differ in conditioning contexts.

Methodology

The training procedure consists of three steps:

1. On-Policy Sampling from the Student. For a given problem \(x\), the student policy samples its own attempted solution:

\[\hat{y} = (\hat{y}_1,\ldots,\hat{y}_{|\hat{y}|}) \sim p_S(\cdot \mid x)\]2. Teacher-Student Distribution Computation. Both policies evaluate the student’s generated trajectory \(\hat{y}\). At each token position \(n\), they compute probability distributions over the next token \(y_n \in \mathcal{V}\) conditioned on the same student prefix \(\hat{y}_{\lt n} = (\hat{y}_1,\ldots,\hat{y}_{n-1})\):

\[p_S(y_n \mid x, \hat{y}_{\lt n}), \qquad p_T(y_n \mid x, y^*, \hat{y}_{\lt n})\]The teacher policy, informed by the correct solution \(y^*\), provides guidance toward reasoning trajectories that lead to the correct answer.

3. Per-Token Distribution Matching. We instantiate a full-vocabulary divergence objective that matches the teacher and student next-token distributions at each position. We define the trajectory-averaged, token-wise divergence:

\[D(p_T \| p_S)(\hat{y} \mid x) = \frac{1}{|\hat{y}|} \sum_{n=1}^{|\hat{y}|} D\left(p_T(\cdot \mid x, y^*, \hat{y}_{\lt n}) \,\|\, p_S(\cdot \mid x, \hat{y}_{\lt n})\right)\]where \(D\) can be any distribution divergence measure such as the generalized Jensen-Shannon divergence \(\text{JSD}_\beta\), defined for a weight \(\beta \in [0, 1]\) as:

\[\text{JSD}_\beta(p_T \| p_S) = \beta D_{\text{KL}}(p_T \| m) + (1 - \beta) D_{\text{KL}}(p_S \| m)\]where \(m = \beta p_T + (1 - \beta) p_S\) is the interpolated mixture distribution. This full-vocabulary formulation provides dense, token-level feedback: the teacher, informed by \(y^*\), exposes the student to the entire distribution over plausible next tokens and guides it toward reasoning paths that lead to the correct answer.

We minimize the expected divergence between teacher and student over on-policy student samples:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{(x,y^*)\sim \mathcal{S}} \left[ \mathbb{E}_{\hat{y}\sim p_S(\cdot|x)} \left[ D(p_T \| p_S)(\hat{y} \mid x) \right] \right]\]Gradients flow only through the student’s logits. The teacher serves as a fixed supervision target, despite both policies sharing the same underlying parameters but differing in their conditioning contexts.

Importantly, we fix the teacher policy to be the initial policy, rather than the currently updating learning policy, as we find this helps stabilize training and implicitly acts as regularization to prevent excessive deviation from the initial policy.

Alternative Objective: Sampled-Token Distillation. As an alternative approach, we can use a policy-gradient formulation that operates only on sampled tokens. For each position \(n\), we define the advantage term:

\[A_n(x, \hat{y}) = \log p_T(\hat{y}_n \mid x, y^*, \hat{y}_{\lt n}) - \log p_S(\hat{y}_n \mid x, \hat{y}_{\lt n})\]and optimize:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = - \mathbb{E}_{(x,y^*) \sim \mathcal{S}} \left[ \mathbb{E}_{\hat{y} \sim p_S(\cdot \mid x)} \left[ \frac{1}{|\hat{y}|} \sum_{n=1}^{|\hat{y}|} A_n(x, \hat{y}) \log p_S(\hat{y}_n \mid x, \hat{y}_{\lt n}) \right] \right]\]where \(A_n(x,\hat{y})\) is treated as a constant (gradients do not flow through the advantage). Compared to the full-vocabulary divergence objective, this sampled-token approach uses the teacher’s log-probabilities to provide dense trajectory-level shaping signals without explicitly matching the full distribution at each step.

OPSD is conceptually similar to Self-Taught Reasoner (STaR)

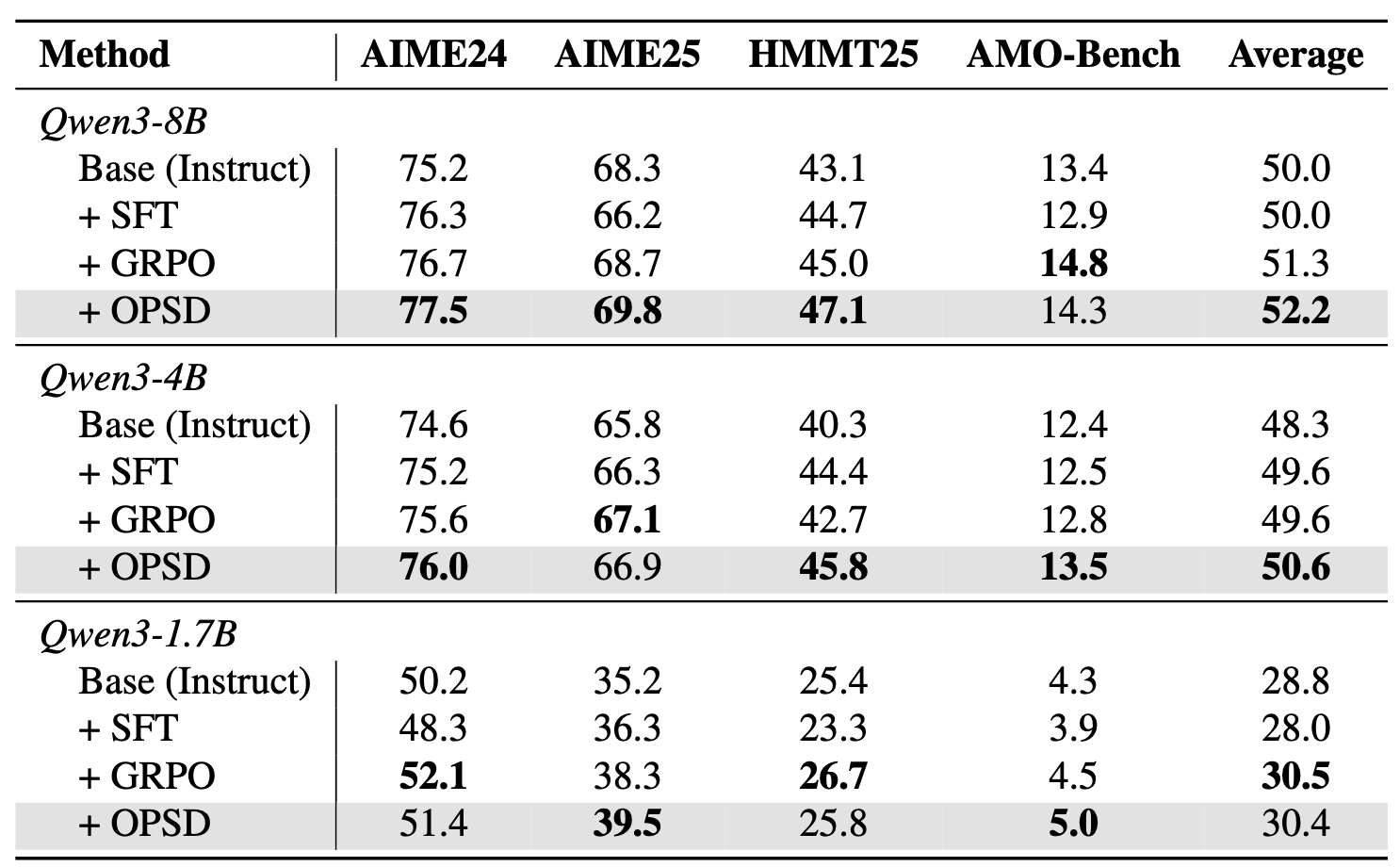

Experimental Results

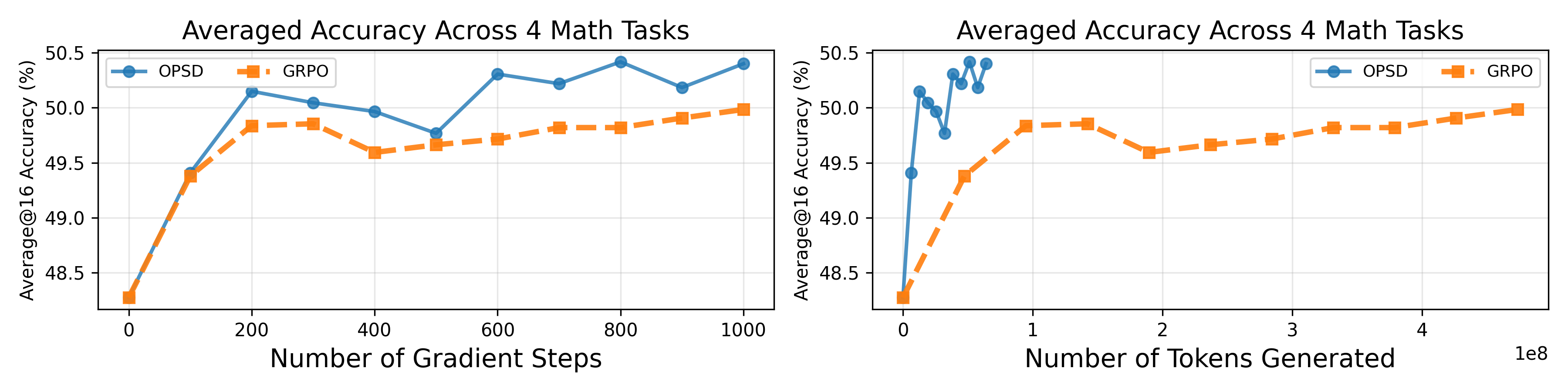

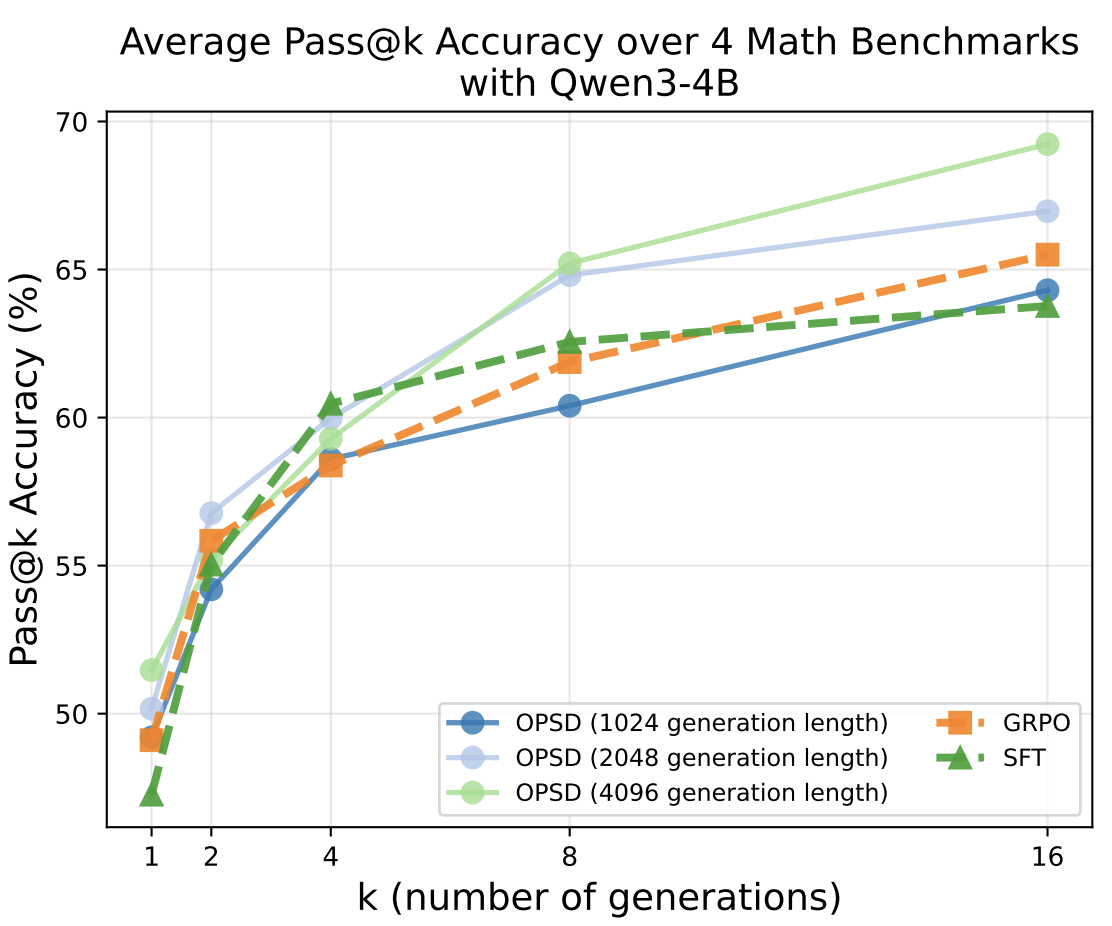

We evaluate OPSD on competition-level mathematical reasoning benchmarks (AIME 2024/2025, HMMT 2025, AMO-Bench) using the Qwen3 model family (1.7B, 4B, and 8B parameters). In the main results below, SFT, GRPO, and OPSD all used the same training datasets from OpenThoughts. For GRPO, we used a 16k generation length and sampled 8 rollouts per problem, while for OPSD, we used only a 2048 generation length for distillation and sampled only 1 rollout per problem. Our results show that across 3 model scales, OPSD has proven to be effective and better than SFT and GRPO, while requiring less computational cost than GRPO.

Computational Efficiency

OPSD achieves superior performance while utilizing 4-8× fewer tokens than GRPO:

These efficiency and efficacy advantages stem from:

- Dense token-level supervision (versus sparse sequence-level rewards).

- Reduced generation budgets (2k tokens versus 16k for GRPO). We hypothesize that the early tokens are more important for distillation than the later tokens, as the earlier tokens can represent more important branching points.

In practice, this translates to reduced training time and lower computational requirements.

Discussions

Effective self-distillation requires sufficient model capacity

OPSD relies on a gap between two conditional views of the same model: the teacher distribution \(p_T(\cdot \mid x, y^\star)\), which has access to the verified solution, and the student distribution \(p_S(\cdot \mid x)\), which does not. For self-distillation to be effective, conditioning on \(y^\star\) must reliably produce a better-informed next-token distribution along the student’s own prefixes \(\hat{y}_{<n}\). This requires the model to be capable of understanding and explaining why a solution is correct, not merely reading it.

When model capacity is insufficient, access to \(y^\star\) does not consistently sharpen the teacher’s distribution or improve token-level guidance. In this regime, the teacher signal is weak or unstable, so matching \(p_T\) provides little benefit and can even introduce noise. As capacity increases, the teacher becomes better at interpreting the problem through the lens of the correct solution and assigning higher probability to reasoning steps that stay on a valid path.

This pattern appears across Qwen3 scales. At 1.7B parameters, OPSD provides only marginal or mixed gains relative to GRPO, while at 4B and 8B, improvements become consistent, suggesting that the teacher signal is now sufficiently informative.

2k distillation tokens with dense supervision can match 16k GRPO generation tokens with sparse rewards

In OPSD, the training objective operates at the token level, so generation length impacts the amount of supervision. We observe that increasing generation length from 1k → 2k → 4k tokens yields consistent performance improvements. OPSD’s dense, token-level supervision is substantially more efficient than GRPO’s sparse, outcome-level rewards. While GRPO requires 16k-token rollouts to achieve strong performance, OPSD matches or exceeds this performance using only 2k tokens for distillation—an 8× reduction in generation length. We hypothesize this efficiency stems from the critical importance of early tokens: these earlier tokens represent key branching points where reasoning paths diverge.

Objective Function Comparison

OPSD can compute the teacher–student discrepancy either as a full-vocabulary divergence \(D(p_T \| p_S)\) at every position or as a sampled-token, policy-gradient-style objective. The key difference is the amount of information passed to the student. Full-vocabulary distillation exposes the student to the teacher’s entire distribution over plausible next tokens, providing fine-grained guidance about which alternatives are more or less compatible with correct reasoning. In contrast, sampled-token objectives only use the probability of the token actually generated. On Qwen3-4B, full-vocabulary logit distillation consistently outperforms the sampled-token objective. The downside is higher memory usage, since vocabulary-sized logits must be stored for many positions.

Results on Qwen3-4B (pass@8 accuracy):

| Method | AIME25 | HMMT25 |

|---|---|---|

| Full-vocabulary | 84.1% | 60.0% |

| Sampled-token | 82.1% | 57.3% |

Limitations and Future Directions

Verification signal integration & group self-distillation. The current OPSD framework does not explicitly incorporate correctness verification because we only generate 2-4k tokens from the student for distillation and they haven’t generated the EoS token. Combining distribution matching with outcome-based verification signals could provide better learning objectives. For example, one could sample a group of full responses, check correctness, and use the model’s own correct reasoning trace to self-distill its incorrect attempts. This would eliminate the reasoning dataset requirement and might be more in-distribution, as the correct reasoning traces are generated by the LLM itself.

Curriculum learning strategies. When problems exceed the model’s comprehension threshold, even the teacher policy cannot provide meaningful supervision when conditioned on the correct answer, because the teacher cannot understand the solution and thus cannot provide a meaningful supervision signal on the student’s response. Adaptive difficulty adjustment—gradually increasing problem complexity as the model improves—could enhance training effectiveness.

Conclusion

On-Policy Self-Distillation demonstrates that sufficiently capable models can provide self-supervision by leveraging their ability to rationalize correct solutions. By conditioning a single model on different contexts—with and without privileged information—OPSD achieves:

- Superior performance compared to supervised fine-tuning

- Comparable or better results than reinforcement learning with 4-8× improved token efficiency

As models continue to scale, this self-teaching capability may become increasingly valuable—enabling more efficient training without the overhead of maintaining separate teacher models or the computational burden of extensive reinforcement learning.

Implementation: The complete paper includes implementation specifications. All experiments employ the Qwen3 model family with LoRA fine-tuning on 8×A100 GPUs.

Citation

If you find this work useful, please consider citing:

@article{zhao2026self,

title={Self-Distilled Reasoner: On-Policy Self-Distillation for Large Language Models},

author={Zhao, Siyan and Xie, Zhihui and Liu, Mengchen and Huang, Jing and Pang, Guan and Chen, Feiyu and Grover, Aditya},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2601.18734},

year={2026}

}